AI cybersecurity review and testing

The goal of this guide is to provide a comprehensive overview of AI penetration testing from a pentester’s perspective, detailing the entire process—from initial client interactions to the specific tests required.

All sources used to create this article are listed in the Sources section and are explained throughout this article.

I will focus on a black-box attacker perspective, with the possibility of incorporating some greybox elements depending on the client’s input.

Methodology

Client objectives and scope definition

In this phase, clarify the client’s goals and establish the scope of the pentest. The client may specify particular AI components, APIs, or systems to focus on. Review the client’s objectives to ensure alignment, and clearly define the boundaries of the testing process, including any restrictions or areas considered out of scope. This ensures that the testing efforts are targeted and meet the client’s expectations.

Questions to Ask:

- What type of AI models are being used? (Predictive ML Models, State-of-the-Art Open Models, External Models - Cf. Model types)

- What is the goal of the AI system? (e.g., prediction, natural language generation, image classification)

- What external interfaces (APIs, web apps) are used to interact with the model?

- Are there third-party services involved?

- Are there any rate-limiting or security controls on the APIs?

- What frameworks and libraries were used in developing the AI model (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch)?

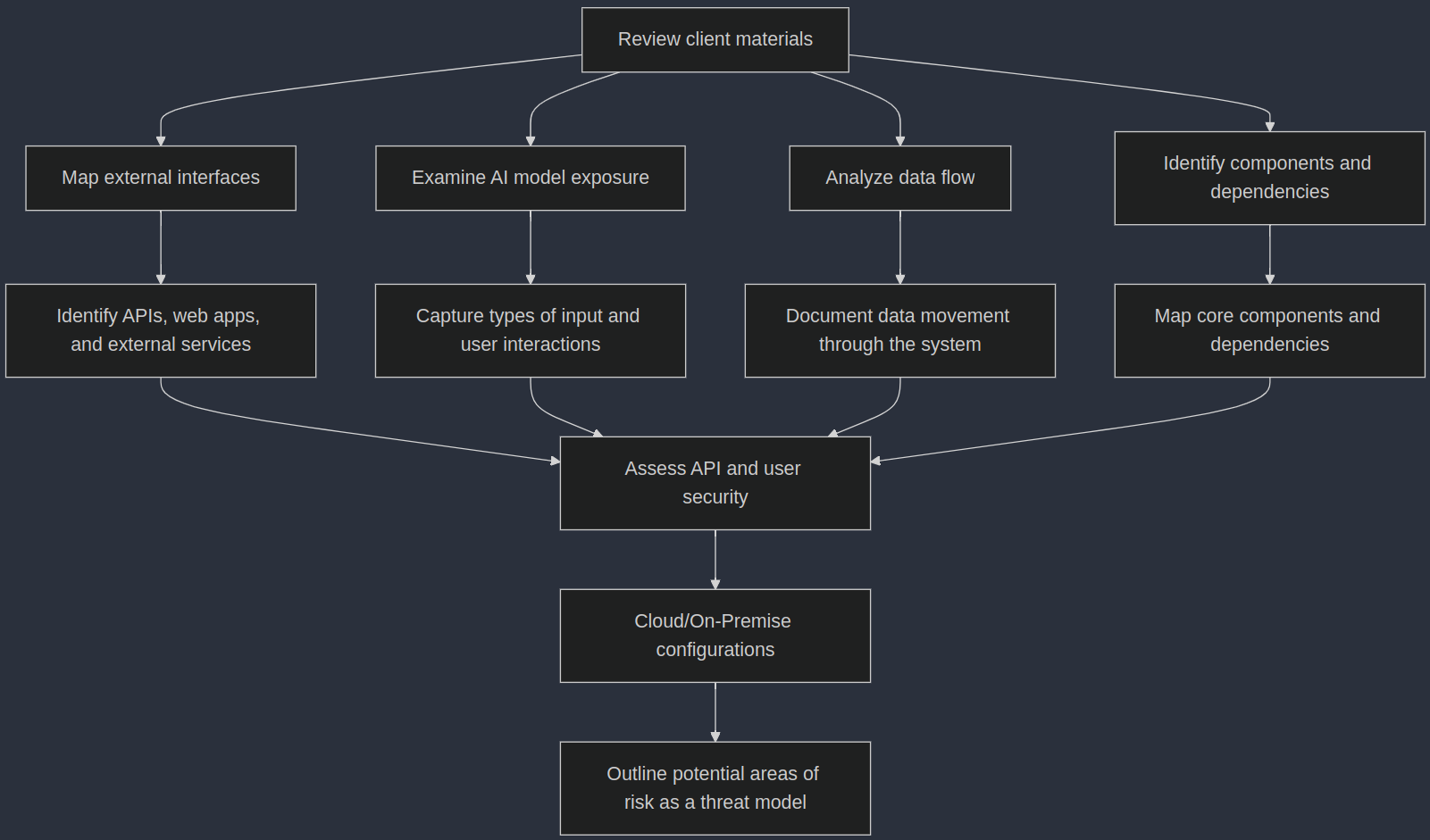

Attack surface identification

In a black-box/gray-box pentest, the client may provide credentials, documentation about the AI system and/or API, schema/diagra, etc. Review all the materials provided to gain a clearer understanding of the tests you’ll need to conduct. Explore the application and map out potential vulnerability areas (mostly experience based).

Key Steps:

- Review client materials: Go through all documents provided by the client to understand the general system design, including data flows, APIs, and security mechanisms. This helps establish a baseline understanding of the environment.

- Map external interfaces: Identify the points where the AI system interacts with external entities, such as APIs, web applications, or third-party services. Focus on documenting how these interfaces are exposed and what potential risks might be associated with them.

- Examine AI model exposure: Understand how the AI model accepts inputs, especially from external sources. Capture details about the types of input it processes and any interactions it has with other systems or users.

- Analyze data flow: Trace the movement of data through the system, from ingestion to processing, storage, and output. Document how data moves between different components and note where sensitive data may be involved.

- Identify components and dependencies: Break down the system into its core components, such as databases, AI models, APIs, and third-party dependencies. Map out which components may interact with others, and take note of external libraries or services in use.

- Assess API and user security: Identify the different roles users can take and how they interact with the system. Document the APIs and user interfaces, focusing on who can access them and how.

- Cloud/On-Premise considerations: Record details about the environment where the system is deployed, whether cloud-based or on-premise. Note key configurations that might affect the security of the deployment, such as network access or infrastructure details.

- Threat modeling: Based on the collected information, start outlining potential areas of risk, that can be explored further during the pentest.

Chain of thought and data gathering

Databricks AI security framework (DSAF)

Model types

First, find out what type of AI models are being built or being used:

- Predictive ML Models: These models focus on traditional machine learning techniques and are specifically designed for structured data. They are trained on your enterprise’s tabular datasets and are typically implemented in Python, often packaged in the MLflow format for deployment. Examples of predictive ML models include scikit-learn, XGBoost, PyTorch, and Hugging Face transformer models. Their primary use is to perform tasks such as regression and classification based on historical data.

- State-of-the-Art Open Models: This category encompasses advanced foundation models that are designed for optimized inference on a variety of tasks, particularly those involving unstructured data. Examples include Meta Llama 3.1-405B-Instruct, BGE-Large, and Mixtral-8x7B, which are available for immediate use with pay-per-token pricing. These models can be deployed for workloads that require performance guarantees and can be fine-tuned for specific applications. Their usage patterns include Foundation Model APIs for large language models (LLMs), retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), pretraining, and fine-tuning, making them suitable for complex applications like natural language processing.

- External Models (Third-Party Services): These models are hosted outside of your organization, typically provided by third-party vendors. Endpoints that serve external models can be centrally governed, allowing organizations to set rate limits and access controls. Examples include widely used foundation models such as OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Anthropic’s Claude. While these models provide easy access to advanced capabilities, they require reliance on the provider’s infrastructure and policies.

Summary of differences:

- Data type: Predictive ML Models focus on structured data, while State-of-the-Art Open Models are suited for unstructured data. External Models can cover both but are accessed via third-party services.

- Complexity: Predictive ML Models are generally simpler, targeting specific prediction tasks, whereas State-of-the-Art Open Models use advanced architectures for complex applications. External Models can vary in complexity but often leverage state-of-the-art techniques.

- Deployment: Predictive ML Models are typically maintained internally, State-of-the-Art Open Models can be deployed locally or accessed as APIs, and External Models are hosted by third parties.

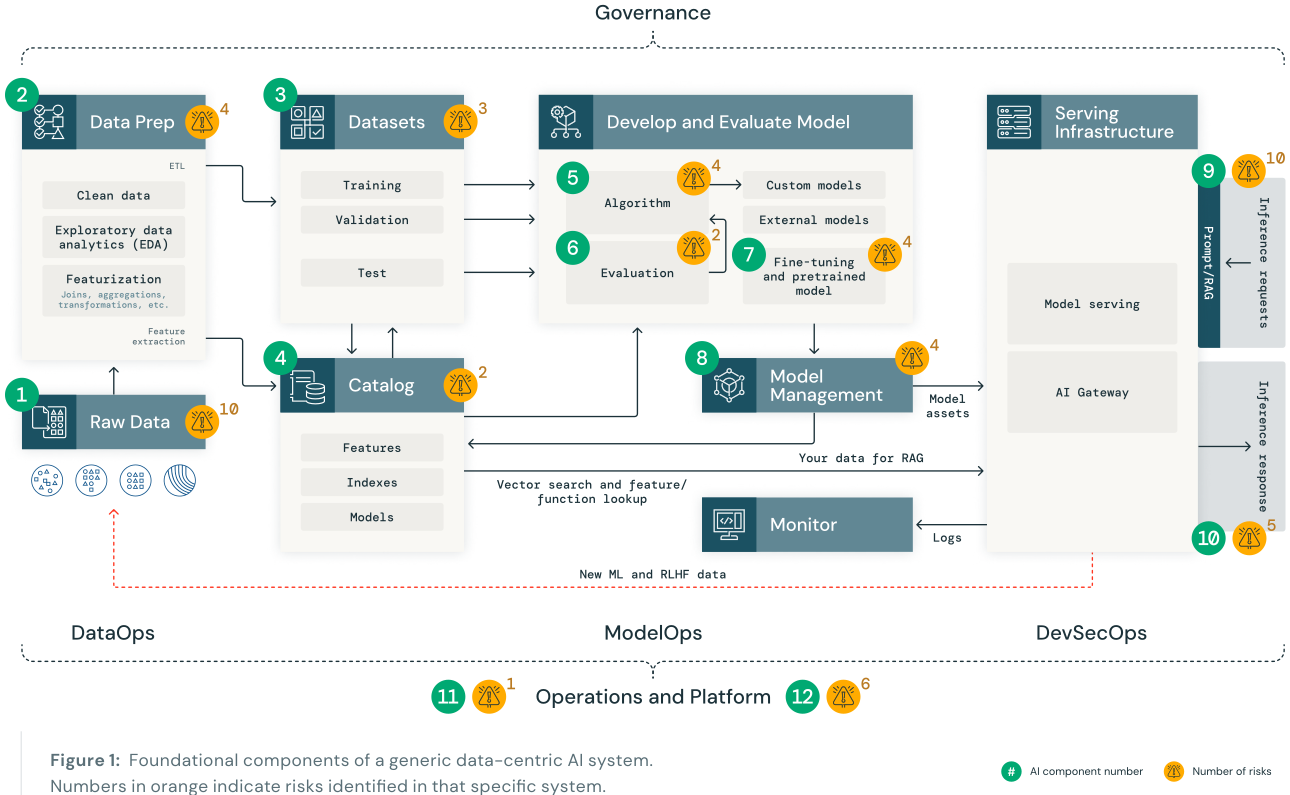

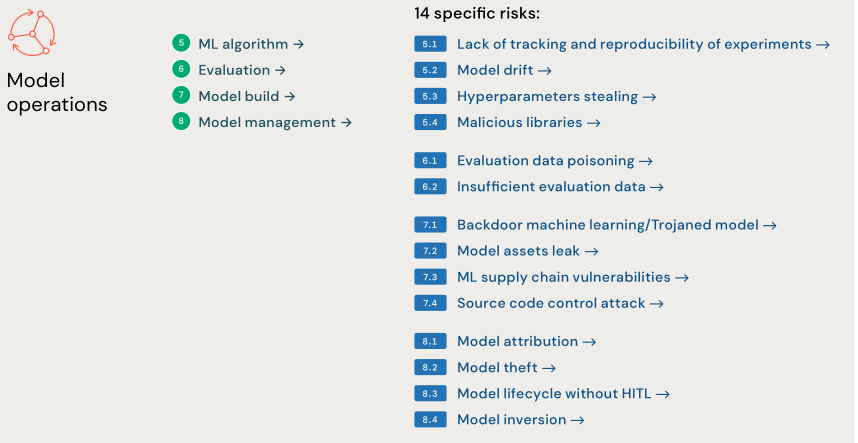

Risks in AI System Components

The DASF starts with a generic AI system in terms of its constituent components and works through generic system risks. By understanding the components, how they work together Executive and the risk analysis of such architecture, an organization concerned about security can get a jump start on determining risks in its specific AI system.

- Data operations (1-4) include ingesting and transforming data and ensuring data security and governance. Good ML models depend on reliable data pipelines and secure DataOps infrastructure.

- Model operations (5-8) include building predictive ML models, acquiring models from a model marketplace, or using LLMs like OpenAI or Foundation Model APIs. Developing a model requires a series of experiments and a way to track and compare the conditions and results of those experiments.

- Model deployment and serving (9 and 10) consists of securely building model images, isolating and securely serving models, automated scaling, rate limiting, and monitoring deployed models. Additionally, it includes feature and function serving, a high-availability, low-latency service for structured data in retrieval augmented generation (RAG) applications, as well as features that are required for other applications, such as models served outside of the platform or any other application that requires features based on data in the catalog.

- Operations and platform (11 and 12) include platform vulnerability management and patching, model isolation and controls to the system, and authorized access to models with security in the architecture. Also included is operational tooling for CI/CD. It ensures the complete lifecycle meets the required standards by keeping the distinct execution environments — development, staging and production — for secure MLOps.

They have identified 55 technical security risks across the 12 components based on the AI model types:

Note: The authors of the framework are aware of emerging risks such as energy-latency attacks, Rowhammer attacks, side-channel attacks, evasion attacks, functional adversarial attacks, and other adversarial examples. However, these are outside the scope of this version of the framework. They may reconsider these and any new novel risks in later versions if they see them becoming material.

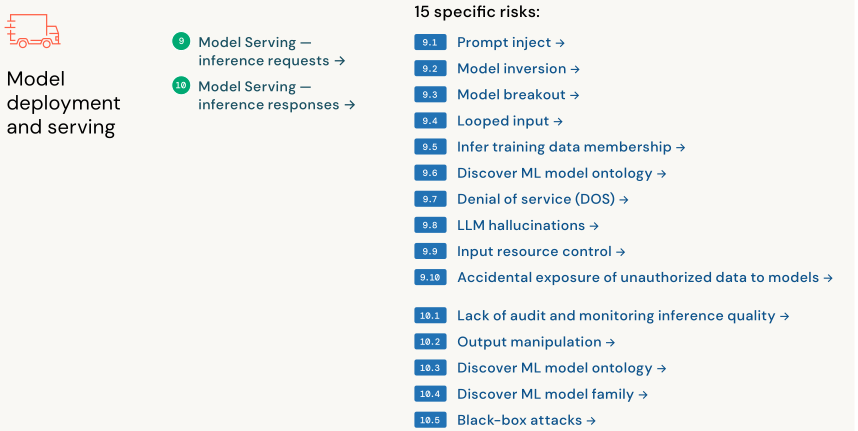

Model deployment and serving

Since the focus is on a black-box/grey-box penetration testing perspective, I’ll review this section as it is the most relevant. I attempted to align each of them with the top 10 for LLM by the OWASP:

Model Serving - inference requests

- Prompt inject - LLM01

- Model inversion - LLM10

- Model breakout - LLM01

- Looped input - LLM09

- Infer training data membership - LLM10

- Discover ML model ontology - LLM10

- Denial of service (DOS) - LLM04

- LLM hallucinations - LLM09

- Input resource control - LLM01

- Accidental exposure of unauthorized data to models - LLM06

Model Serving - inference responses

- Lack of audit and monitring inference quality - None

- Output manipulation - LLM06

- Discover ML model ontology - LLM10

- Discover ML model family - LLM10

- Black-box attacks - None

The classification may be inaccurate, and certain areas remain somewhat vague. However, I plan to use parts of it to help develop a testing methodology.

Regarding a black-box/grey-box approach, using the OWASP LLM Top 10 as a basis, the classification is almost fully represented, though there are still some gaps, especially around LLM07 and LLM08, that I think should be included in these tests.

On a personal note

- LLM10 is well-represented, and I found it to be the most challenging aspect to test. Despite being last in the classification, it remains crucial to address, though further research is needed.

- The issue of “Lack of audit and monitoring for inference quality” is particularly difficult to tackle from a penetration testing perspective

- Finally, “Black-box attacks” should always be performed; however, it doesn’t fit within the OWASP LLM Top 10, as it represents a category of its own that is more closely related to web/API implementations rather than AI-specific vulnerabilities.

OWASP Top 10 for LLM

OWASP is widely recognized and utilized by many clients and companies, making it a relevant framework for developing a testing methodology. To start, I will identify which of the OWASP Top 10 vulnerabilities are applicable in a blackbox or greybox configuration.

Here’s a breakdown of which are particularly relevant, along with explanations:

- LLM01: Prompt Injection

This is one of the most accessible attacks in blackbox/greybox testing, as it primarily requires manipulating input prompts. Testers can experiment with crafted prompts, exploring how the model behaves and if it follows unintended instructions or reveals system behavior through crafted inputs.

| Examples |

|---|

| Causing the LLM to reveal confidential information |

| Bypassing safety filters |

| Executing unauthorized actions |

- LLM02: Insecure Output Handling

You can inspect how the application processes and displays LLM responses, looking for potential output sanitization issues (e.g., Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) or injection vulnerabilities). Limited schema access could help map where LLM output integrates with other backend components, helping identify injection points for testing secure output handling.

| Examples |

|---|

| Executing malicious code generated by the LLM. |

| Displaying inappropriate or misleading information to users. |

| Triggering unintended actions in connected systems. |

- LLM04: Model Denial of Service

Testing the system’s rate-limiting and throttling mechanisms is feasible. By inputting complex, resource-intensive prompts, you can assess whether the application is resilient to input flooding or if it’s prone to service disruption under load.

| Examples |

|---|

| Overloading with complex or recursive prompts |

| Flooding the system with high-frequency requests |

| Triggering resource-intensive tasks |

- LLM06: Sensitive Information Disclosure

Carefully monitor the LLM’s output for any unintended leakage of sensitive information, even if you don’t have access to its training data. Even limited schema knowledge may reveal sensitive fields that could be targeted to elicit potentially sensitive data through prompts. Credentials provide opportunities to probe if the model exposes any sensitive user information, application metadata, or internal details that should remain private.

| Examples |

|---|

| Exposing confidential user data |

| Leaking proprietary algorithms |

| Revealing internal system details |

- LLM07: Insecure Plugin Design

If any plugins or integrations are visible, you could analyze their data flow for secure input handling, proper permissions, and access control. Since plugins often handle sensitive tasks, testing for vulnerabilities in input validation, command execution, and access restrictions is feasible with limited schema access.

| Examples |

|---|

| Injecting unauthorized commands via plugins |

| Accessing restricted system functions |

| Causing privilege escalation |

- LLM08: Excessive Agency

In a blackbox scenario, understanding the LLM’s agency and its potential for unintended actions can be challenging. Testing whether the LLM is given excessive permissions that could lead to unintended actions or overreach requires a thorough examination of its capabilities and access levels, ensuring that it does not have the ability to perform actions beyond its intended scope, which could compromise system integrity or lead to unauthorized data manipulation.

| Examples |

|---|

| Performing unauthorized actions autonomously |

| Interfering with critical systems |

| Escalating permissions without oversight |

- LLM09: Overreliance

When relying on an LLM with an opaque decision-making process, it’s crucial to implement strong mechanisms to verify the accuracy of its outputs, as blind trust can lead to poor decisions and security vulnerabilities. To test for overreliance, testers should validate the LLM’s responses against known correct answers, simulate high-stakes scenarios to assess decision alignment, and ensure that critical decisions involve human oversight for validation.

| Examples |

|---|

| Accepting incorrect information from the LLM as fact |

| Failing to recognize biases or limitations in the LLM’s responses |

| Making critical decisions without validation |

- LLM10: Model Theft

Protecting against model theft is essential, especially when using third-party LLM APIs or open-source models. Attackers might try to extract model parameters or replicate the LLM’s functionality through repeated queries or other techniques.

| Examples |

|---|

| Extracting model weights through prompts |

| Copying model parameters |

| Rebuilding the model through extensive interaction |

In this constrained blackbox/greybox scenario, LLM03 (Training Data Poisoning) and LLM05 (Supply Chain Compromise) are less applicable. Testing these requires deeper insights into the model’s data origins, the supply chain components, or the actual model parameters—details likely inaccessible with only a few schemas and login credentials.